Good to Know: Anti-establishment orientation

A key dividing line in politics isn't just ideology, but also people’s fundamental trust in the system itself.

JAN ZILINSKY

Anti-establishment movements and parties have gained notable traction in many democracies. The rise of populist parties in Italy, France, the Netherlands, and much of Eastern Europe provides prominent examples. These developments, however, are perhaps overshadowed by the multiple presidential campaigns (and presidencies) of Donald Trump in the United States. Trump’s three candidacies were characterized by promises to “drain the swamp” – and the many allegations of conspiracies against him and the nation.

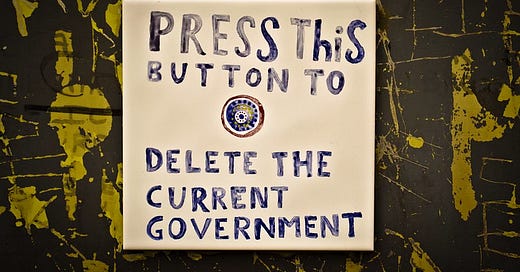

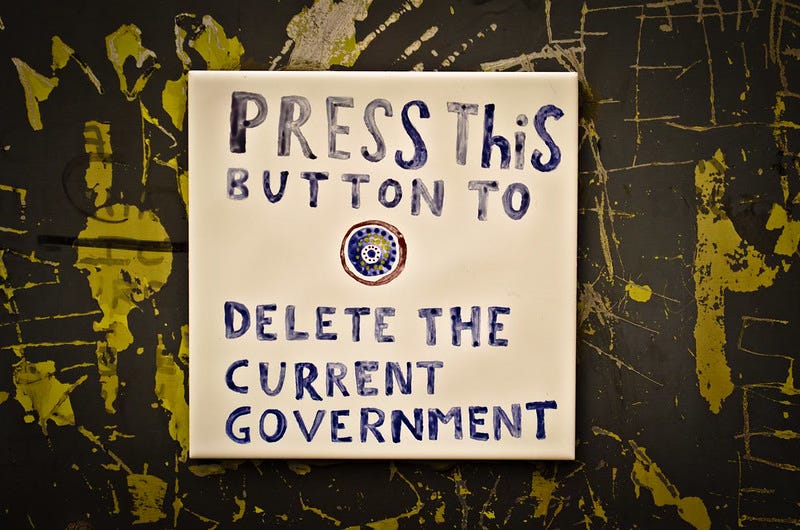

Anti-establishment movements or parties are typically characterized by their rejection of some institutions and elites. They often position themselves as outsiders who represent regular people, understand their grievances, and promise to fight against a corrupt system.

What makes anti-establishment movements so popular?

The prominence of anti-establishment campaigns, and even styles of governing, raises important questions about what fuels their popularity.

Anti-elite rhetoric typically originates from political challengers. But the broad success of these movements suggests that something deeper resonates among voters themselves. Is there a distinct, deeply held political orientation driving widespread support for critics of “the system”?

Political science research suggests that such an orientation indeed exists. And it is distinct from conventional ideology, involves a profound and enduring suspicion towards established institutions, carries significant implications, and exists on a continuum. The research indicates that having a high degree of anti-establishment mindset correlates with a range of behaviors and beliefs.

It is helpful to think about such an orientation as a spectrum. One on end are strong supporters of the existing system. At the other are its most vehement critics. Researchers have now identified several intertwined components that underpin this orientation: conspiratorial thinking, sympathies with populism, and a rigid view of politics.

Conspiracism – and how to leverage it

At its heart, conspiracism is the belief that powerful entities secretly orchestrate events to serve their own interests at the expense of ordinary people. Scholars like Adam Enders and Joseph Uscinski measure conspiracism by assessing the extent to which people agree with statements such as “Much of our lives are being controlled by plots hatched in secret places” and “Even though we live in a democracy, a few people will always run things anyway.”

In the United States, Donald Trump’s political career provides numerous examples of leveraging conspiracist sentiment. More than a decade ago, he fueled accusations about Barack Obama’s birthplace and helped launch the “birther” conspiracy. During his first term in office, Trump frequently blamed the “deep state” for the administration’s setbacks. After losing the 2020 election, he blamed a widespread conspiracy against him, both at the ballot box and in subsequent legal proceedings, which he framed as persecution.

One of the goals of conspiracism is to activate a general suspicion of hidden elite manipulations. Conspiracist claims are particularly potent as they offer compelling, albeit often simplistic, narratives for how the establishment allegedly maintains control and engages in sinister and secret plots. The claim, thus, is that the established system does not truly represent “the people” – a concern central to populist thought.

Populism – “people” vs. “elites”

Political scientists generally describe populism as a political logic or ideology that suggests a fundamental moral dichotomy. So a virtuous, unified, and often victimized “people” are battling against a corrupt, self-serving “elite” (the establishment).

Researchers can measure populist sentiment by gauging agreement or disagreement with survey questions designed to tap into this “people-versus-elite” worldview and the desire for direct popular sovereignty. Examples include: “I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a professional politician,” “Elected officials talk too much and take too little action,” or “The established elite and politicians have often betrayed the people.”

A Manichean (and binary) view of politics

A Manichean worldview, in the political context, refers to the tendency to perceive political struggles in stark, binary terms. This view leaves little room for nuance, legitimate disagreement, or compromise.

Those who are part of “the establishment,” or those who defend it, thus, don’t merely hold different opinions. Those on the outside may actively cast elites as morally depraved. Political engagement thus becomes a moral crusade against perceived evil forces.

Political scientists can measure this moralistic outlook by inviting survey respondents to indicate their agreement with statements such as, “Politics is a battle between good and evil,” or “What people call compromise in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.”

More than distrust of the government

It’s important to distinguish this orientation from everyday political discontent. Mainstream parties frequently campaign on promises of change and better things to come. While criticism of government elites is valid in many cases, an anti-establishment orientation typically runs deeper than situational frustration among voters.

For example, a voter might strongly oppose their country’s leadership based on perceived incompetence or economic corruption, without necessarily viewing the leadership as part of a morally bankrupt system.

Furthermore, general skepticism towards the government isn’t new, according to historical data. American National Election Studies surveys in the 1990s revealed that a majority of Americans believed “public officials don’t care what people think” (a sentiment about half of the survey participants shared during the Reagan administration). This finding indicates that such negative evaluations alone do not equate to a deep-seated anti-establishment orientation.

Influence on political behavior

Ultimately, this anti-establishment orientation, forged from conspiracism, populism, and a good-vs-evil worldview, is not just a fringe belief. Anti-establishment politics transcends ordinary dissent – and has become a powerful lens for interpreting the world. Understanding this concept is important for understanding political outcomes because this viewpoint has tangible and often destabilizing consequences.

Crucially, just as populism can be right wing or left wing, a conspiracy mindset can also support beliefs in both left-wing and right-wing conspiracy theories. Globally, there appears to be no correlation between the traditional left-right ideology and conspiracism. Of course, this viewpoint can correlate with votes for specific parties or figures – those perceived to give a voice to deep-seated anti-establishment (and at times paranoid) intuitions.

Some research has found that an anti-establishment orientation is linked to greater support for political violence as a means to achieve political goals, and with a greater likelihood of believing misinformation. Those with anti-establishment views also tend to have colder evaluations of both the Democratic and the Republican parties, perceiving both parties as complicit in a corrupt system.

But critics of parties, even if they run on major party tickets, do receive greater support from anti-establishment voters. In recent years, this proved true for both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. While we may think of strong cynicism of the existing system as politically demobilizing, both Sanders and Trump have shown that’s an incorrect stereotype. Critics of the establishment are ready to participate in politics if they think such participation may lead to shaking up the system.

Jan Zilinsky is a 2025-2026 Good Authority fellow.

Related Good Authority posts

Margaret Appleby, “Conspiracy theories are spreading wildly. Why now?” From May 2022, looking at how social media, polarization, and political anxiety help fuel the spread of conspiracy theories.

E.J. Graff, “Everything you need to know about the worldwide rise of populism.” From November 2016, a compilation of articles covering populism around the globe.

Alexander Kustov and Yaoyao Dai, “Good to Know: Populism.” From March 2025, exploring the rise of populism, and how political scientists define the term.

Pippa Norris, “It’s not just Trump. Authoritarian populism is rising across the West. Here’s why.” From March 2016, examining the wave of authoritarian populists who found growing support in several Western democracies.

John Sides, “Are we exaggerating populism’s threat to democracy?” From September 2024, discussing the findings in Democracy’s Resilience to Populism’s Threat, by political scientist Kurt Weyland.

John Sides, “Right-wing populist parties have risen. Populism hasn’t.” From January 2024, a closer look at new research on the rise of populist parties.

Further reading

Matthew Flinders and Markus Hinterleitner, “Party Politics vs. Grievance Politics: Competing Modes of Representative Democracy,” Society (2022), 59(6): 672–81.

Jan-Werner Müller, What Is Populism? (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Joseph Uscinski, Adam Enders, Amanda Diekman, John Funchion, Casey Klofstad, Sandra Kuebler, Manohar Murthi, et al., 2022, “The Psychological and Political Correlates of Conspiracy Theory Beliefs,” Scientific Reports (2022), 12(1): 21672.

Joseph E. Uscinski, Adam M. Enders, Michelle I. Seelig, Casey A. Klofstad, John R. Funchion, Caleb Everett, Stefan Wuchty, Kamal Premaratne, and Manohar N. Murthi, “American Politics in Two Dimensions: Partisan and Ideological Identities versus Anti‐Establishment Orientations,” American Journal of Political Science, 2021,65(4): 877–95.

Kostiantyn Yanchenko, Artur Lipiński, and Giorgos Venizelos, “We, the… Elites? Anti-Elitism of Governing Populist Parties in Poland, Greece, and Ukraine.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, May 12, 2025.