Good to Know: Why do we need government?

The Constitutional framers believed that weak governments could be just as dangerous to individual freedom as powerful ones.

ERIC GONZALEZ JUENKE

In The Federalist Papers, No. 51, James Madison explores why newly independent America needed an effective and well-constructed government:

But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.

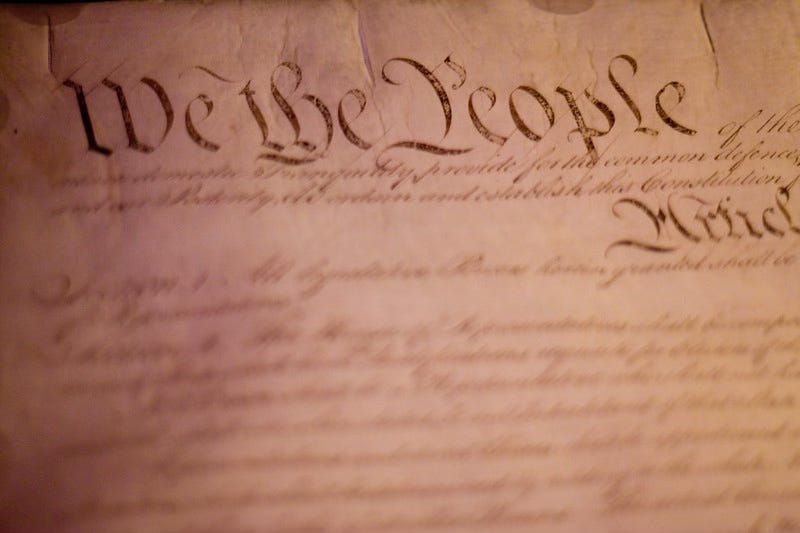

A unique moment in political history

When 55 state delegates arrived in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, they faced a rare opportunity. They had been called to fix the Articles of Confederation, an ineffective “league of friendship” between the 13 state governments. Historically, national governments tend to develop this way, building in piecemeal fashion from what had existed before. Alternatively, new governments were also brought in by conquering armies. These delegates – the “Framers of the Constitution” – instead opted to create a new national government from scratch, attempting to turn the 13 independent and “united” states into the nation of the United States.

The difficulty of their task was enormous. Asking newly independent states to give up some of their sovereignty to an unknown but potentially dangerous new “novelty” government forced many political leaders of the era to ask a big question. And it’s the very same question that students and citizens today often ask political science instructors:

Why do we need government?

Americans are well acquainted with all of the ways in which the Framers feared government and protected us from its powers. But often we neglect the problem that brought the delegates to Philadelphia in the first place: Weak and ineffective government also puts our lives and liberties at risk.

How a strong government protects individual liberties

The supporters of the Constitution – the “federalists” – and their “anti-federalist” opponents in the states debated about the size and scope of America’s government. They all agreed, however, that government itself was essential to preserving the blessings of individual liberty. In Federalist Papers, No. 2, John Jay writes:

Nothing is more certain than the indispensable necessity of government, and it is equally undeniable, that whenever and however it is instituted, the people must cede to it some of their natural rights in order to vest it with requisite powers.

Think about that carefully. America’s founding leaders thought that to truly be free, individuals must give up some of their freedom. It sounds like a rhetorical trick – and indeed, many modern-day libertarian and anarchist thinkers believe this idea is a fiction created to “enslave a free people.” Fiction or not, leaders of the early American republic took this concept as a matter of political faith.

In the absence of government, you will still be governed

This view conforms with how modern social scientists think about the general purpose of government. Government, at a bare minimum, is the entity with a monopolyon violence. Government solves the collective action problem of common defense that arises in a state of constant war or violence. Economist Mancur Olson, for instance, defined government as a “stationary bandit” that protects citizens from roving bandits in exchange for taxes.

These minimalist definitions of government follow from social contract theories more familiar to the Framers of the Constitution, from authors like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. In Common Sense, the influential January 1776 pamphlet that spurred colonists towards revolution, Thomas Paine called government a “necessary evil.” For authors like this, freedom from government leads to anarchy, and if there is any individual freedom found there it is “nasty, brutish and short.”

“Establish justice… promote the general welfare”

The Framers believed the states needed a new government to solve many other collective action problems as well, being so clear as to write them all down in the Preamble to the Constitution. In Federalist Papers 11 and 12, Hamilton discusses the economic benefits of a strong national government. Government creates efficiencies, he writes – not only with foreign trade, but also with interstate commerce. Hamilton famously wanted a national bank, a precursor to the Federal Reserve system, to create market stability so American business could thrive. The idea that government creates and enforces economic rules and therefore lowers transaction costs for businesses is also supported by modern social science theories.

Over time, politicians from all sides have argued that expanding national and state governments will also generate better economic, social, and private freedoms. National defense concerns, for example, were one reason the federal government poured money into higher education in response to the Sputnik launch in the late 1950s. This funding, in turn, massively expanded university enrollment and scientific research. Cold War fears also accelerated America’s national highway system and the creation of the precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. And politicians have also used national defense as a pretext to both expand and contract the nation’s openness to immigration throughout U.S. history.

For Americans, national, state, and local governments have an impact on just about everything, from the roads we drive on, to the air we breathe, to the safety we often enjoy, to the food we eat, and the ways we communicate with one another. Some see this as massive government overreach. Many of the Framers would instead be amazed at the size and success of the industry and individual freedom their fledgling government created. Our ability to pursue private opportunities, to move and think freely, and to do business with others is both freedom from government as well as protection by government.

Between Scylla and Charybdis

We spend a lot of time in government classes talking about the ingenious ways in which the Framers of the U.S. Constitution broke up the political system to protect our liberties. Specific protections include the separation of powers, checks and balances, the Bill of Rights, and a bicameral legislature. Some students inevitably ask, “If government is so scary, why not just get rid of it?” We forget that the prospect of a weak and too-small government was far more terrifying in 1787. After all, the Framers were not sent to Philadelphia for a summer picnic.

The American political experiment is not just about navigating rough seas to avoid the looming dangers akin to Scylla, a monster that once threatened Odysseus and his ship. It is not just a fear of too much government. It is just as much about evading the other dangers of Charybdis – in this case, the void that develops when government is too small and ineffective.

Students and citizens alike must understand the seriousness of both fears as each generation takes up the struggle of American politics. The vacuum of weak government will be filled by tyranny from other nations, or private companies wanting to monopolize markets and control government. U.S. history also offers plenty of examples of the factional ways in which Americans tyrannize each other.

Attempting to solve this dilemma – creating a government strong enough to protect people’s liberties, but not so strong that it could be used to take away these liberties – is the genius of the Constitutional project. The ongoing transformation of the U.S. Constitution into a better reflection of its ideals throughout the nation’s 250-year history continues this legacy.

Related Good Authority posts:

Jenna Bednar, “Of course Trump’s authority isn’t ‘total.’ Here are 3 myths about how federalism works.” From June 2020, discussing President Trump’s highly centralized concept of federalism during the early months of the pandemic.

Sarah Binder, “Could the U.S. government shut down in March?” A closer look at the spring 2025 government shutdown threat, explaining why Congress holds the power of the purse – and whether the president has the authority to second-guess those spending decisions.

Alan Coffee, “150 years ago, Frederick Douglass predicted the United States’ dilemma today.” From August 2021, reflecting on the deep U.S. political divisions and the many parallels with 19th century American politics.

Sarah Gershon, Nadia E. Brown, Larry Berman, and Bruce Murphy, “The U.S. has veered toward – and away from – democracy over time.” The authors of the new ninth edition of “Approaching Democracy: American Government in Times of Challenge” discuss the January 2021 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol within the broader context of how American democracy has expanded, constricted, failed, and succeeded throughout history.

Alexandra Guisinger, “Good to Know: The Federal Reserve and U.S. monetary policy.” From January 2024, explaining the role of the U.S. central bank, and why the Fed’s independence matters.

Danielle Lupton, Jessica Blankshain, David T. Burbach, Lindsay P. Cohn, and Theo Milonopoulos, “Can the president deploy the military inside the United States?” From December 2024, discussing the limits of presidential authority under the Constitution and federal law – in the context of President-elect Trump’s plans to mobilize the U.S. military to aid mass deportations.

Andrew Rudalevige, “Too many Americans know too little about the Constitution. Here’s how you can fix that.” From 2017, introducing Bowdoin College’s “Founding Principles” video series (see the full series on PBS). The first video focuses on the most basic of the U.S. Constitution’s principles: the separation of powers.

Andrew Rudalevige, “Good to Know: Impeachment.” From January 2024, as Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives held an impeachment inquiry against President Joe Biden.

Heather Sullivan, “You want to live in a Freedom City? Take a closer look at Honduras.” Amid the hype in 2025 about the benefits that deregulated charter cities might offer in the United States, here’s a cautionary tale about the experimental city of Próspera in Honduras.

Further reading and resources:

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers(Penguin Random House, 2012).

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Simon and Schuster, 2008).

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon and Schuster, 2011).

Suzanne Mettler, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy (Chicago University Press, 2011).

Meghan Ming Francis, Civil Rights and the Making of the Modern American State (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Charles de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Douglas North, “Transaction Costs, Institutions and Economic Performance“ (International Center for Economic Growth, 1992).

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action (Harvard University Press, 1971).

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Penguin Random House, 2015).

John Ragosta, For the People, For the Country: Patrick Henry’s Final Political Battle (University of Virginia Press, 2023).

Andrew Sharp (ed.), The English Levellers (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Emily Thorson, The Invented State: Policy Misperceptions in the American Public (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Eric Gonzalez Juenke is a 2025-2026 Good Authority fellow.